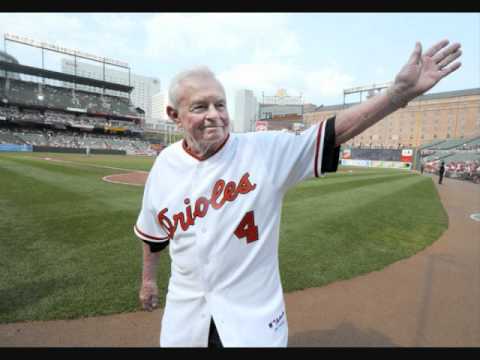

The lasting visions of Earl Weaver always will include an irate man with hat askew, kicking dirt and screaming at an umpire. But the Hall of Fame manager was more innovator than instigator.

Weaver, who won four American League pennants and a World Series during his 17 seasons as manager of the Baltimore Orioles, died early today after collapsing during an Orioles-sponsored cruise. He was 82.

It was Weaver who pioneered use of radar guns to measure pitchers' velocity. It was Weaver who kept a stack of index cards to keep track of pitcher-vs.-batter matchups, long before the computerization of the game's statistics.

And, of course, it was Weaver whose 94 ejections – often flamboyant and even once before a game even started – that made him most memorable. That total still is an American League record, topped in the majors only be the recently retired Bobby Cox and Hall of Famer John McGraw.

"The job of arguing with the umpire belongs to the manager," Weaver once said. "It won't hurt the team if he gets thrown out of the game."

But he also said, in a 1986 interview, "On my tombstone just write, 'The sorest loser that ever lived.' "

The Orioles are holding their annual FanFest this weekend and a moment of silence was held as the event opened this morning.

"Earl Weaver stands alone as the greatest manager in the history of the Baltimore Orioles and one of the greatest in the history of the game," Orioles owner Peter Angelos said in a statement released by the team. "Earl made his passion for the Orioles known both on and off the field. This is a sad day."

Weaver, who never played in the majors, replaced Hank Bauer as Baltimore manager midway through the 1968 season. His 48-34 record the rest of that season wasn't enough to catch the Detroit Tigers in the AL race, but the Orioles' second-place finish was a message to the rest of the league. Weaver's teams would win the next three pennants and the 1970 World Series.

"Bad ballplayers make good managers," Weaver said. "Not the other way around. … A manager's job is simple. For 162 games, you try not to screw up all the smart stuff your organization did last December."

Weaver's organization, the one he joined in 1957 at manager of a minor league team in Fitzgerald, Ga.

He worked his way through the Baltimore farm system and was added to the major league coaching staff in 1987.

The Orioles team he inherited certainly was talented. It included future Hall of Famers Frank Robinson and Brooks Robinson. Another, pitcher Jim Palmer, would be promoted from the minors in 1969, the year Weaver's heavily favored team lost the World Series to the New York Mets.

He got his World Series victory a year later, winning seven of eight post-season games – a three-game sweep of Minnesota in the AL Championship Series and a five-game World Series triumph over Cincinnati.

Weaver's relationship with his players often was as colorful as his celebrated battles with umpires.

Palmer once said, "The only thing Earl knows about a curveball is that he couldn't hit it."

But Weaver hardly was worried about his relationships.

"I don't know if I said 10 words to Frank Robinson while he played for me," Weaver said.

But those players understood the Weaver was ahead of his time.

"He used to keep these little cards with what guys used to hit off certain guys," said current Washington Nationals manager Davey Johnson, who was an Oriole in Weaver's first five seasons as manager. "This guy was 2-for-6. This guy was 1-for-10. I tried to explain to him, 'Earl, you know what the standard deviation curve is?' He says, 'What the hell is that.' "

But he knew how to use players, making frequent use of platoons, having a left- and a right-handed hitter share a position. He also would list as the designated hitter in his starting lineup a pitcher who he didn't plan to use, then insert a real hitter when that spot in the batting order came up.

Weaver, who won four American League pennants and a World Series during his 17 seasons as manager of the Baltimore Orioles, died early today after collapsing during an Orioles-sponsored cruise. He was 82.

It was Weaver who pioneered use of radar guns to measure pitchers' velocity. It was Weaver who kept a stack of index cards to keep track of pitcher-vs.-batter matchups, long before the computerization of the game's statistics.

And, of course, it was Weaver whose 94 ejections – often flamboyant and even once before a game even started – that made him most memorable. That total still is an American League record, topped in the majors only be the recently retired Bobby Cox and Hall of Famer John McGraw.

"The job of arguing with the umpire belongs to the manager," Weaver once said. "It won't hurt the team if he gets thrown out of the game."

But he also said, in a 1986 interview, "On my tombstone just write, 'The sorest loser that ever lived.' "

The Orioles are holding their annual FanFest this weekend and a moment of silence was held as the event opened this morning.

"Earl Weaver stands alone as the greatest manager in the history of the Baltimore Orioles and one of the greatest in the history of the game," Orioles owner Peter Angelos said in a statement released by the team. "Earl made his passion for the Orioles known both on and off the field. This is a sad day."

Weaver, who never played in the majors, replaced Hank Bauer as Baltimore manager midway through the 1968 season. His 48-34 record the rest of that season wasn't enough to catch the Detroit Tigers in the AL race, but the Orioles' second-place finish was a message to the rest of the league. Weaver's teams would win the next three pennants and the 1970 World Series.

"Bad ballplayers make good managers," Weaver said. "Not the other way around. … A manager's job is simple. For 162 games, you try not to screw up all the smart stuff your organization did last December."

Weaver's organization, the one he joined in 1957 at manager of a minor league team in Fitzgerald, Ga.

He worked his way through the Baltimore farm system and was added to the major league coaching staff in 1987.

The Orioles team he inherited certainly was talented. It included future Hall of Famers Frank Robinson and Brooks Robinson. Another, pitcher Jim Palmer, would be promoted from the minors in 1969, the year Weaver's heavily favored team lost the World Series to the New York Mets.

He got his World Series victory a year later, winning seven of eight post-season games – a three-game sweep of Minnesota in the AL Championship Series and a five-game World Series triumph over Cincinnati.

Weaver's relationship with his players often was as colorful as his celebrated battles with umpires.

Palmer once said, "The only thing Earl knows about a curveball is that he couldn't hit it."

But Weaver hardly was worried about his relationships.

"I don't know if I said 10 words to Frank Robinson while he played for me," Weaver said.

But those players understood the Weaver was ahead of his time.

"He used to keep these little cards with what guys used to hit off certain guys," said current Washington Nationals manager Davey Johnson, who was an Oriole in Weaver's first five seasons as manager. "This guy was 2-for-6. This guy was 1-for-10. I tried to explain to him, 'Earl, you know what the standard deviation curve is?' He says, 'What the hell is that.' "

But he knew how to use players, making frequent use of platoons, having a left- and a right-handed hitter share a position. He also would list as the designated hitter in his starting lineup a pitcher who he didn't plan to use, then insert a real hitter when that spot in the batting order came up.

Sad Leftwich is sad.

Never got to see him coach in person but have watched enough of his highlights and past games to realize how much he meant to this franchise. I hope the orioles do something to honor him this year on opening day.

Comment